Real Example Cleaning

Overview

Teaching: 10 min

Exercises: 10 minQuestions

How do you clean an example dataset?

How do you deal with missing data?

How do you fix column type mismatches?

Objectives

Clean an example dataset using both previously described concepts and some new ones

Cleaning Real Data

The previous episodes have focused on key concepts with small datasets and/or made up data. However, these examples can only take you so far. For this reason the remaining lessons and examples will be focused on an actual dataset from the Hawaiian Ocean Time-Series (HOT) data website (Link to HOT Data Website). This website allows you to query data generated by the time-series through various modules.

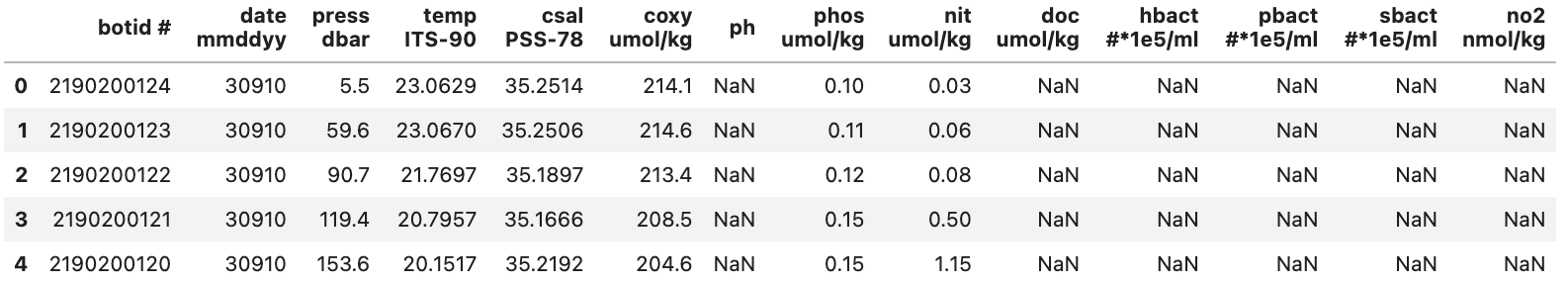

The Hawaiian Ocean Time-Series has been collecting samples from station ALOHA located just North of Oahu since 1988. The map below shows the exact location where the samples we will be using originate from.

(Original image from: https://www.soest.hawaii.edu/HOT_WOCE/bath_HOT_Hawaii.html)

Going forward we are going to be using data from HOT between the 1st of January 2010 to the 1st of January 2020. This particular data we are going to be utilizing comes from bottle extractions between depths 0 to 500m. The environmental variables that we will be looking at include:

| Column name | Environmental Variable |

|---|---|

| botid # | Bottle ID |

| date mmddyy | Date |

| press dbar | Pressure |

| temp ITS-90 | Temperature |

| csal PSS-78 | Salinity |

| coxy umol/kg | Oxygen concentration |

| ph | pH |

| phos umol/kg | Phosphate concentration |

| nit umol/kg | Nitrate + Nitrite concentration |

| no2 nmol/kg | Nitrite concentration |

| doc umol/kg | Dissolved Organic Carbon concentration |

| hbact #*1e5/ml | Heterotrophic Bacteria concentration |

| pbact #*1e5/ml | Prochlorococcus numbers |

| sbact #*1e5/ml | Synechococcus numbers |

The data contains over 20000 individual samples. To analyze the data we are going to clean it up. Then, in the next episode we will analyze and visualize it. To do this we will be using some of tricks we have already learn while also introducing some new things. Note: The dataset we are using has been modified from its original format to reduce the amount of cleaning up we need to do.

Cleaning Up

DataFrame Content Cleanup

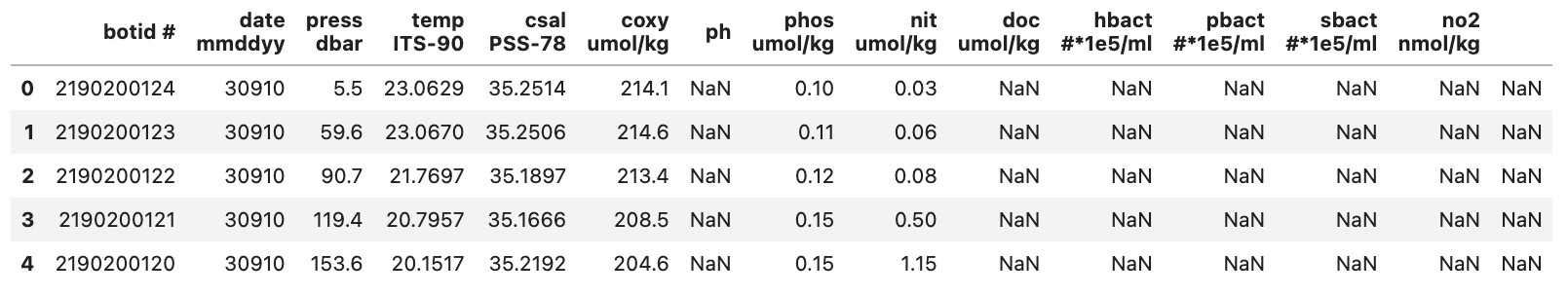

During our initial clean up we will only load in the first few rows of our dataset entire DataFrame. This will make it easier to work with and less daunting.

pd.read_csv("./data/hot_dogs_data.csv", nrows=5)

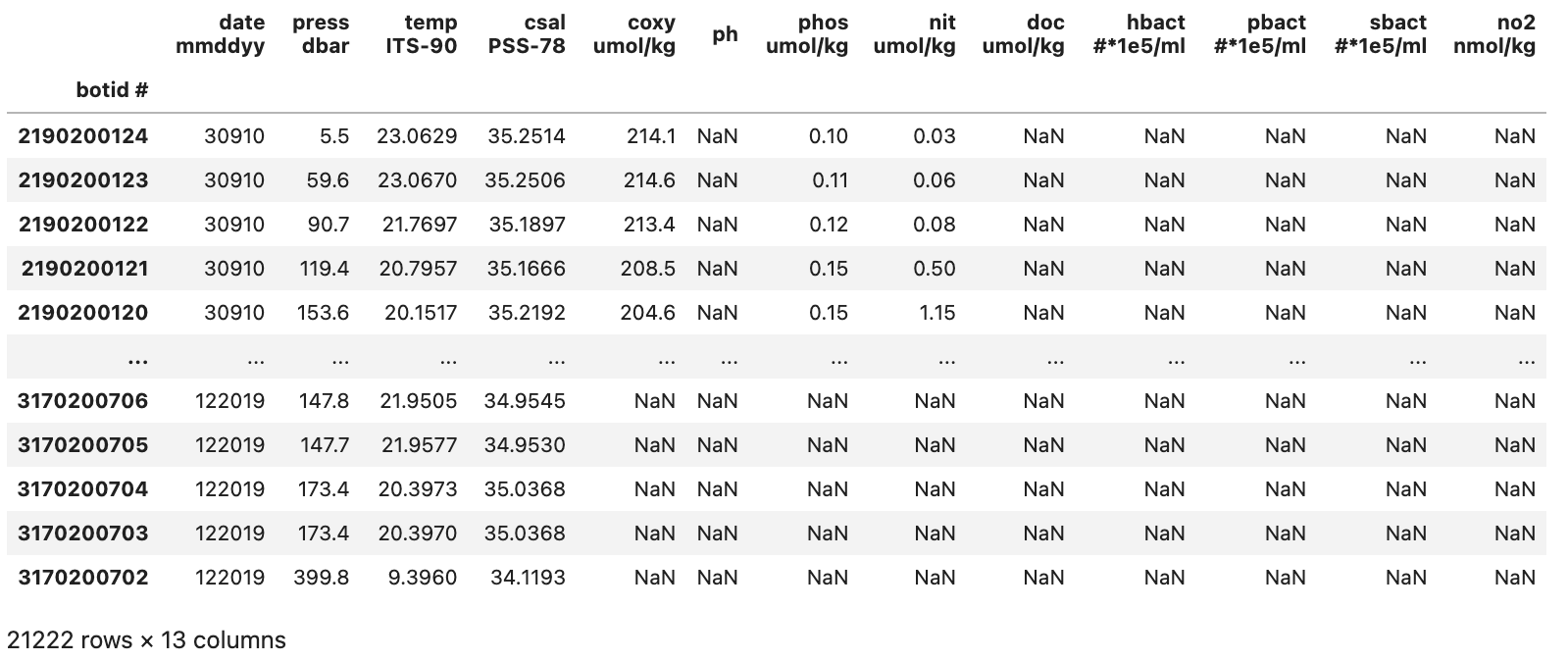

This will show us the DataFrame seen below:

From this we can see a few things:

- There are a lot of -9 values

- This is likely to denote Null values in the dataset

- The last column (to the right of the no2 column) doesn’t seem to contain a header or any data

Both of these issues can easily be fixed using Pandas and things we’ve learn previously.

To start off lets fix the first problem we saw which was was the large number of -9 values in the dataset. These are especially strange for some of the columns e.g. how can there be a negative concentration of hbact i.e. heterotrophic bacteria? This is a stand in for places where no measurement was obtained.

Treating -9 values as NaN values when loading data

To start off try fixing the read_csv() method so that all -9 values are treated as NaN values. If you are stuck try going back to the episode on this topic (Link to loading data episode).

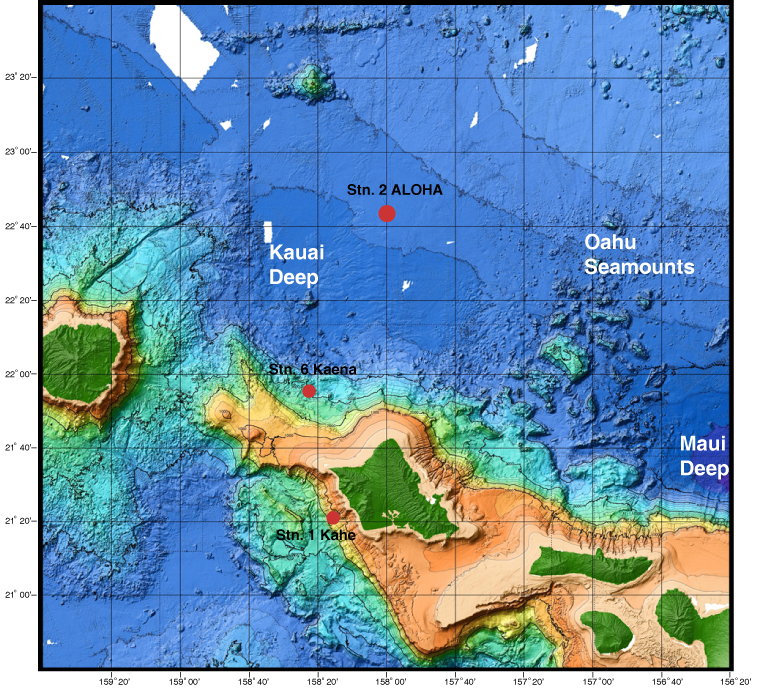

Solution

To fix this we can add the parameter

na_values=-9to theread_csv()method giving us the following code bit.pd.read_csv("./data/hot_dogs_data.csv", nrows=5, na_values=-9)Below shows how our

DataFramenow looks:

With this we have fixed the problematic -9 values from our initial DataFrame.

Temperature Column

The temperature column could technically contain -9 values. However, all temperature measurements were above 0 so this is not an issue.

The second problem we identified was that there was an extra column (with no header) made up of only NaN values. This is probably an issue with the original file and if we were to take a look at the raw .csv file we find that each row ends with a ‘,’. This causes read_csv to assume that there is another column with no data since it looks for a new line character (\n) to denote when to start a new row.

There are various methods to deal with this. However, we are going to use a relative simple method that we’ve already learn. As we discussed in a previous episode pandas DataFrames have a method to drop columns (or indexes) called drop. Where if we provide it with the correct inputs it can drop a column based on its name. Knowing this we can chain our read_csv method with the drop method so that we load in the blank column and then immediately remove it.

Dropping the blank column

The final command we will be using can be seen below. However, the columns parameter is missing any entries in its list of columns to drop. You will be fixing this by adding the name of the column that is empty (hint: the name isn’t actually empty).

pd.read_csv("./data/hot_dogs_data.csv", nrows=5, na_values=-9).drop(columns=[])To get the name of the column we will want to utilize a

DataFrameattribute that we have already discussed that provides us with the list of names in the same order they occur in theDataFrame. If you are stuck check the previous episode where we discussed this (Link to previous episode).Solution

To get the name of the columns we can simply access the

columnsSeriesattribute that everDataFramehas. This can be done either through chaining it after ourread_csvmethod or by store it in a variable and then call the method using that variable. Below we use the chain approach.pd.read_csv("./data/hot_dogs_data.csv", nrows=5, na_values=-9).columnsIndex(['botid #', ' date mmddyy', ' press dbar', ' temp ITS-90', ' csal PSS-78', ' coxy umol/kg', ' ph', ' phos umol/kg', ' nit umol/kg', ' doc umol/kg', ' hbact #*1e5/ml', ' pbact #*1e5/ml', ' sbact #*1e5/ml', ' no2 nmol/kg', ' '], dtype='object')The last entry in the

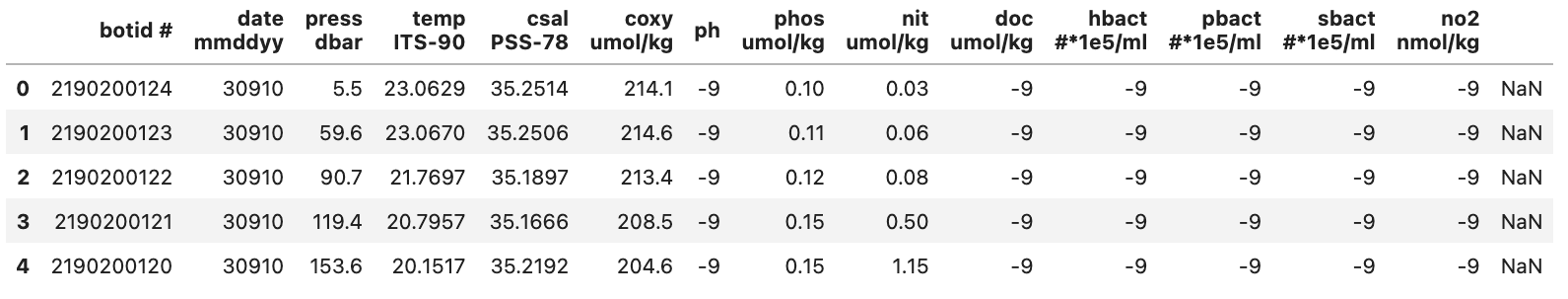

Seriesis our ‘blank’ column i.e.' '. We add this as the only entry to our drop method and get the following code bit.pd.read_csv("./data/hot_dogs_data.csv", nrows=5, na_values=-9).drop(columns=[" "], axis=1)This then gives us the output

DataFrameseen below:

With this we have fixed some of the initial issues related to our dataset. It should be noted that there might still exist other issues with our dataset since we have only relied on the first few rows.

Column Names

Checking the

columnsattribute even if nothing immediately looks wrong can be good in order to spot e.g. blank spaces around column names that can lead to issues.

One final thing that we are going to do that is not quite “clean up” but nonetheless important is to set our index column when we load the data. The column we are going to use for this is the ‘botid #’ column. We can also remove the nrows=5 parameter since we want to load the whole DataFrame starting in the next section.

Setting the index column when loading data

To set the index column we can use a parameter in

read_csvthat was mentioned in a previous episode. See if you can remember it! If you run into trouble you can take a look at the previous episode where it was mentioned (Link to prev episode).Solution

To set the index column when we load the data we just have to add the parameter

index_coland set it to ‘botid #’. Note: we have removed thenrows=5parameter in the code bit below since we no longer need it.pd.read_csv("./data/hot_dogs_data.csv", na_values=-9, index_col="botid #").drop(columns=[" "], axis=1)

This gives us a somewhat cleaned up DataFrame that looks like the image below:

With our initial cleanup done we can now save the current version of our DataFrame to the df variable. This df variable will be used for the next two sections.

DataFrame Column Types

Now that we have fixed the initial issues we could glean from an initial look at the data we can take a look at the types that Pandas assumed for each of our columns. To do this we can access the .dtypes attribute.

df.dtypes

date mmddyy int64

time hhmmss int64

press dbar float64

temp ITS-90 float64

csal PSS-78 float64

coxy umol/kg float64

ph float64

phos umol/kg float64

nit umol/kg float64

doc umol/kg float64

hbact #*1e5/ml float64

pbact #*1e5/ml float64

sbact #*1e5/ml float64

no2 nmol/kg float64

dtype: object

Most of the columns have the correct type with the exception of the ‘date mmddyy’ column that has the int64 type. Pandas has a built in type to format date and time columns and conversion of the date column to this datetime type will help us later on.

To change the type of a column from an int64 to a datetime type is a bit more difficult than e.g. a int64 to float64 conversion. This is because we both need to tell Pandas the type that we want it to convert the column’s data to and the format that it is in. For our data this is MMDDYY which we can give to Pandas using format='%m%d%y'. This format parameter can be very complicated but is based on native python more information can be found on the to_datetime method docs (Link to datetime method docs).

The code bit below creates a new column called ‘date’ that contains the same data for each row as is found in the ‘date mmddyy’ column but instead with the datetime64 type. It will not delete the original ‘date mmddyy’ column.

df["collection_date"] = pd.to_datetime(df['date mmddyy'], format='%m%d%y')

df.dtypes

date mmddyy int64

time hhmmss int64

press dbar float64

temp ITS-90 float64

csal PSS-78 float64

coxy umol/kg float64

ph float64

phos umol/kg float64

nit umol/kg float64

doc umol/kg float64

hbact #*1e5/ml float64

pbact #*1e5/ml float64

sbact #*1e5/ml float64

no2 nmol/kg float64

date datetime64[ns]

dtype: object

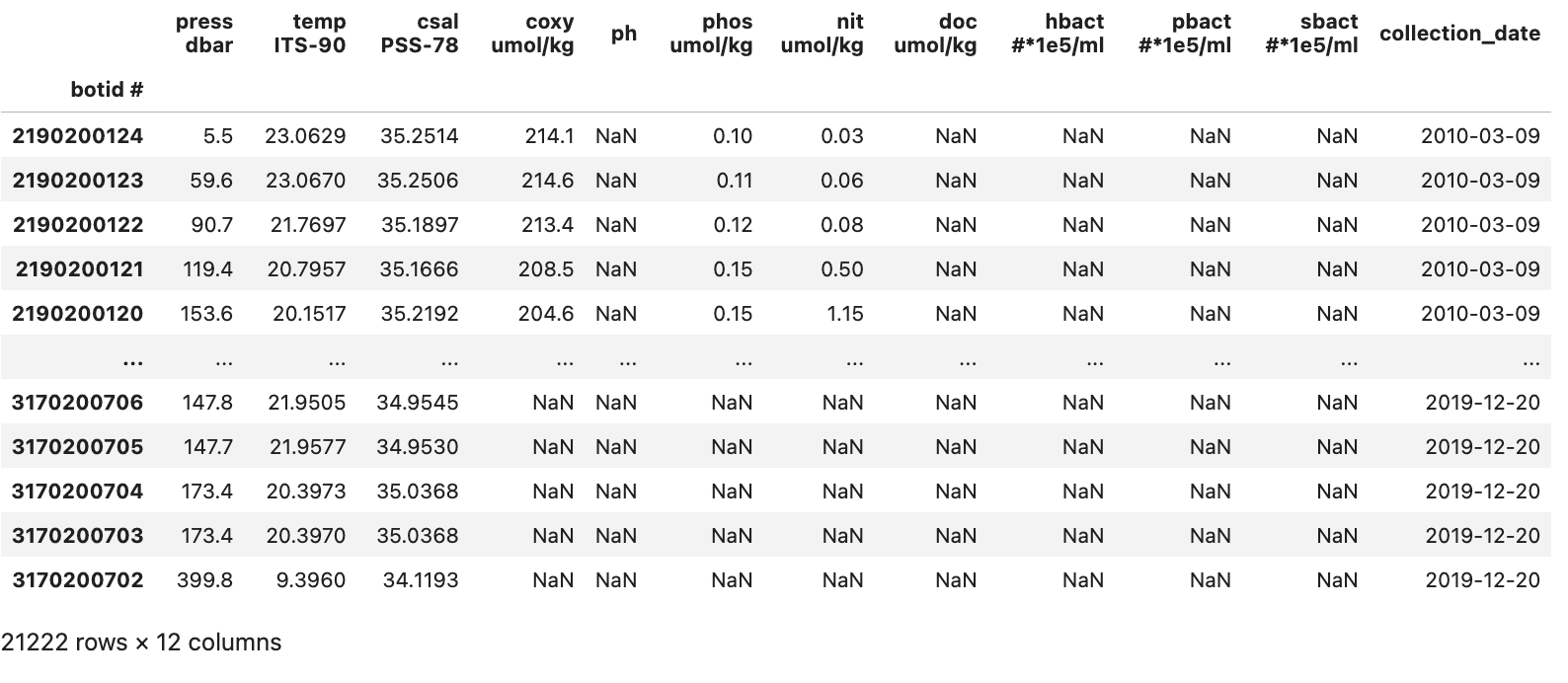

We can see from the output that we have all of our previous columns with the addition of a ‘date’ column with the type datetime64. If we take a look at the new column we can see that it has a different formatting compared to the ‘date mmddyy’ column

df["collection_date"]

botid #

2190200124 2010-03-09

2190200123 2010-03-09

2190200122 2010-03-09

2190200121 2010-03-09

2190200120 2010-03-09

...

3170200706 2019-12-20

3170200705 2019-12-20

3170200704 2019-12-20

3170200703 2019-12-20

3170200702 2019-12-20

Name: collection_date, Length: 21222, dtype: datetime64[ns]

Now that we’ve added this column (which contains the same data as found in ‘date mmddyy’ just in a different format) there is no need for the original date mmddyy column so we can drop it.

df = df.drop(columns=["date mmddyy"])

DataFrame Overview

A final thing we will want to do before moving on to the analysis episode is to get an overview of our DataFrame as a final way of checking to see if anything is wrong. To do this we can use the describe() method which we discussed earlier.

df.describe()

time hhmmss press dbar temp ITS-90 csal PSS-78 coxy umol/kg \

count 21222.000000 21222.000000 21222.000000 21210.000000 3727.000000

mean 103238.977523 119.381105 21.570407 35.020524 198.222297

std 68253.013809 120.193833 4.961006 0.382516 27.787824

min 3.000000 0.800000 6.055800 34.018800 30.900000

25% 40625.000000 25.500000 20.625800 34.922500 199.350000

50% 101309.000000 89.700000 23.109450 35.138700 207.200000

75% 154822.000000 150.900000 24.742175 35.281500 212.000000

max 235954.000000 500.000000 28.240100 35.556400 230.900000

ph phos umol/kg nit umol/kg doc umol/kg hbact #*1e5/ml \

count 885.000000 2259.000000 2253.000000 868.000000 750.000000

mean 7.956939 0.448331 5.505113 63.688341 3.933479

std 0.158210 0.638772 9.159562 10.287748 1.173908

min 7.366000 0.000000 0.000000 41.270000 1.481000

25% 7.898000 0.070000 0.020000 55.467500 2.976250

50% 8.035000 0.120000 0.240000 67.395000 4.042000

75% 8.065000 0.520000 6.620000 72.282500 4.809500

max 8.105000 2.610000 35.490000 80.460000 7.889000

pbact #*1e5/ml sbact #*1e5/ml no2 nmol/kg

count 749.000000 750.000000 0.0

mean 1.364606 0.010932 NaN

std 0.938620 0.011851 NaN

min 0.000000 0.000000 NaN

25% 0.337000 0.000000 NaN

50% 1.643000 0.009000 NaN

75% 2.176000 0.016000 NaN

max 3.555000 0.091000 NaN

A look at the output shows us that the ‘no2 nmol/kg’ column does not contain any useable data based on its count value being 0. This then leads to the NaN for e.g. the min and max values. Since this column doesn’t contain any information of interest we can drop it to clean up our DataFrame.

df = df.drop(columns=["no2 nmol/kg"])

With this done our data is reasonably cleaned up and we have the DataFrame seen in the image below:

We can now move on to the analysis and visualization of the data in our DataFrame.

Summary

With this we’ve clean up our initial dataset. To summarize we have:

- Replaced the -9 placeholder for Null values with NaN values

- Fixed an issue with an extra column containing no data

- Added a custom row index

- Converted the data in ‘date mmddyy’ to a Pandas supported datetime type

- Dropped two columns:

- ‘date mmddyy’ column since the new ‘date’ column contains the same data but in a better type

- ‘no2 nmol/kg’ column since it contained no data

Key Points

Cleaning a dataset is an iterative process that can require multiple passes

Keep in mind to restart the kernel when cleaning a dataset to make sure that your code encompasses all the cleaning needed.