Overview to Workshop and Introduction to Climate Science

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 70 minQuestions

What is a Climate Science?

What is climate vs. weather?

How can machine learning help model climate?

Objectives

Understand the current advancements and limitations of climate research

| Lesson | Teaching | Lesson | Main Questions | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning | 10 mins | 10 mins | What is machine learning? What are some powerful applications of these tools? | Establish background context for machine learning models |

| Climate | 5 mins | 0 mins | What does it mean to study climate? What is climate vs. weather? | Establish a basic understanding of the field of climate |

| Climate Obstacles | 5 mins | 0 mins | What are the biggest barriers to climate science? How can we establish context with little data, train models in a changing world? | Establish important context for obstacles in the field of climate |

| The El Nino Southern Oscillation | 5 mins | 5 mins | What is ENSO? Why is it important to our understanding of climate/climate change? | |

| Machine Learning in Climate: Resources | 5 mins | 5 mins | What are some resources with climate time-scale data? | List of websites and archives that contain large, publicly available data |

| Machine Learning in Climate: Data Processing | 5 mins | 5 mins | Best methods of data processing? | Dealing with missing data, outliers, time scale variability |

| Machine Learning in Climate: LSTM Models | 15 mins | 15 mins | What is a Long-Short Term Model? How can we use this for time-series analysis? | Using buoy data within the ENSO 3.4 index, we’ll train, test, and then assess an LSTM model |

Intro: What is Climate Science?

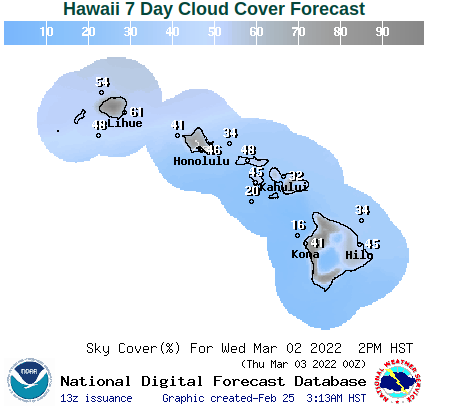

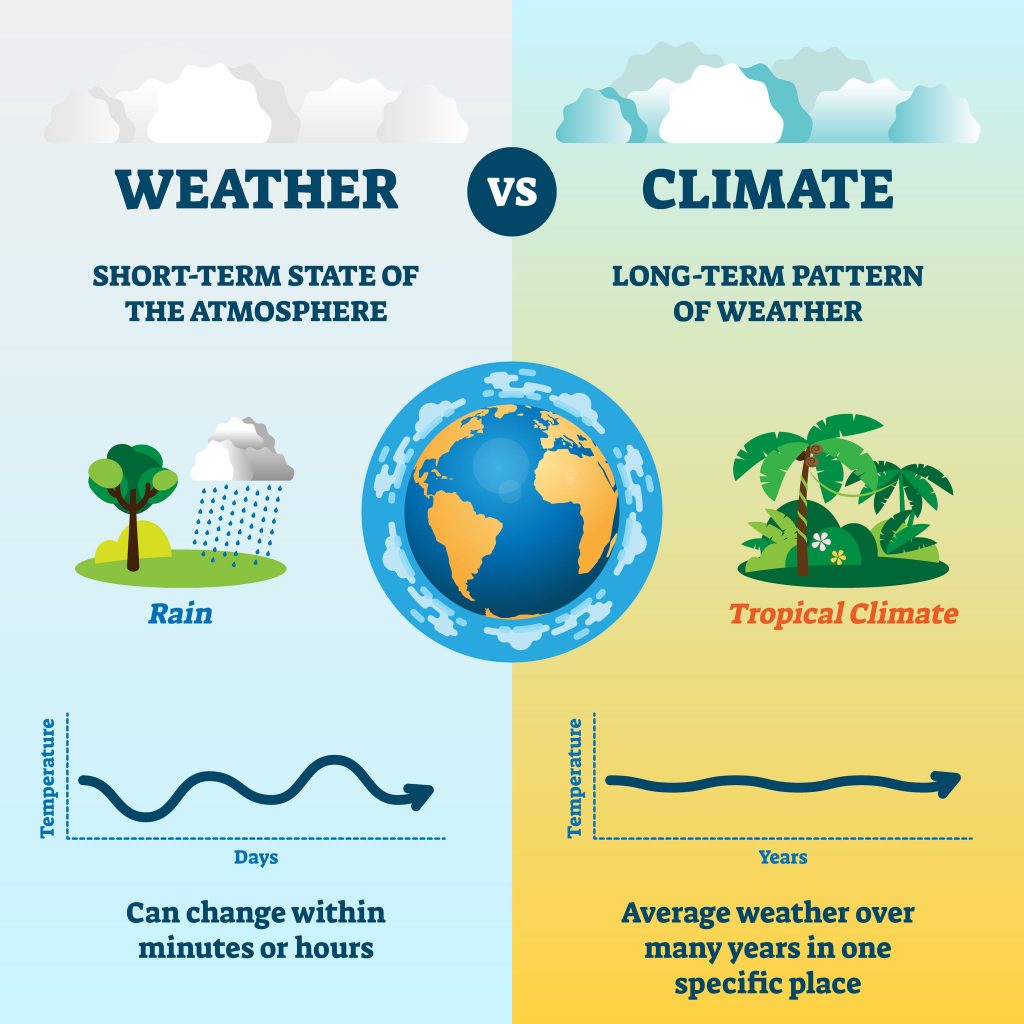

“Climate change” is the phrase of the decade, and is rapidly shaping the future of humanity. But what is climate, say, versus weather? And how are they connected? Weather is the state of the atmosphere at a place and time with regards heat, dryness, sunshine, wind, rain, and other conditions. Weather describes the immediate state of these conditions, or the state of the atmosphere at a specific place and time. For example, today’s weather (02/25/22) is supposed to have a high of 80 degrees F, around 60% relative humidity, scattered cumulus clouds and a minimal chance of rain. Climate, on the other hand, is the long-term description of typically a more broad region. Climate describes the generalized patterns experienced over a larger geographic region. Hawaii’s climate, for example, is around 85 degrees F with scattered trade-wind rain showers in the summer time, and around 75 degrees F with broader, more less weaker trade winds and more substantial rain in the winter. Climate does not describe every day perfectly, however.

Climate science, therefore, is not the study of individual weather events, but the study of long-term patterns and changes of patterns in weather and atmospheric conditions. Typically, climate science refers to the study of global climate and how the world as a whole is changing, however, climate scientists can often have specific regions of study as well. When we refer to climate change, we assess how the long term patterns across the world are changing compared to typical, historical values. Climate change can be described as changes in average seasonal temperatures to changes in precipitation, changes in sea ice coverage, changes in cloud coverage, etc. Anything large geographic and time scale change with relation to weather can be described as climate change if there is long term data to support the identified changes.

One of the most important concepts of cliamte science is that singular weather events do not define, confirm, or negate the evidence of changing climate.

(Source: Australian Climate Education Office)

(Source: Australian Climate Education Office)

Machine Learning and Applications to Weather/Climate Models

Machine learning tools are increasingly important for modeling data in climate science. This tutorial will guide you through two common uses: downscaling and emulation. We will first describe these approaches generally, then step through a particular example of each.

Downscaling

Predictions of future weather and climate rely on simulations of the Earth’s atmosphere on a global scale. Despite being run on the world’s largest supercomputers, these simulations are still crude approximations. Machine learning can help predict future (or historical) climate (or weather) through a method called statistical downscaling. In climate science, “downscaling” refers to increasing the resolution of data, either in the spatial and/or temporal dimensions. Think of taking a blurry low-resolution image and enhancing it to get a higher-resolution image. In machine learning this is known as “super-resolution”; in climate science it is called downscaling.

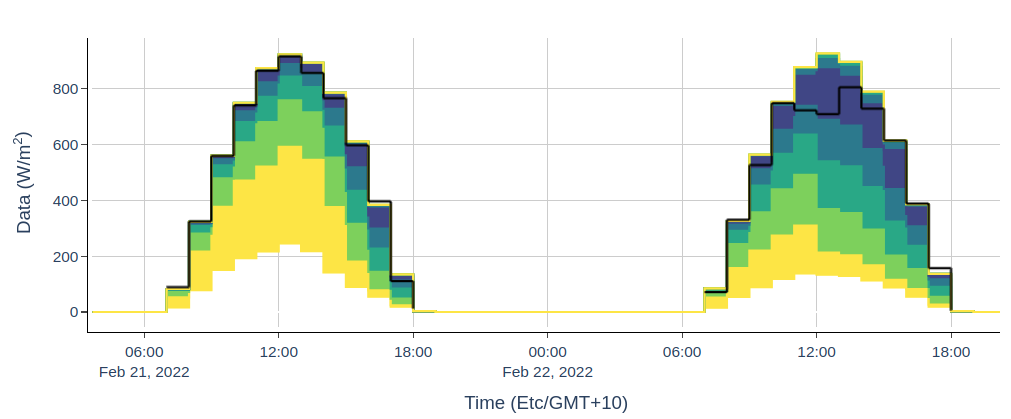

There are two main appraoches to downscaling: dynamical and statistical. Dynamical downscaling will not be discussed today — it relies on physics simulations. Statistical downscaling uses data-driven models to predict high-resolution data from low-resolution data. For example, we can train a machine learning model that ingests course-grained weather forecasts and predicts minute-by-minute forecasts specific location; the example below demonstrates this method used to for day-ahead forecasts of hourly solar-irradiance for Kona Hawaii.

We can apply the same approach on a climatological scale to predict average temperatures and rainfall on the Hawaiian islands under different climate change scenarios. To train these models, we combine historical observations of these variables with low-resolution model outputs. While this tutorial does not explicitly demonstrate the downscaling approach, the models in the tutorial can be adapted to this task.

Emulation

The simulations used to predict weather and climate rely on physics models to predict how the atmosphere will evolve over many small time steps. To increase the simulation’s accuracy, one requires an increase in spatiotemporal resolution of the simulations, and thus additional computation. An alternative approach is to use machine learning as a fast approximation to these simulations, where we use a statistal model to predict the state of the atmosphere at the next time step. Such a model can be trained on simulation, and can learn to emulate the physics model (it is also known as a surrogate model). It is possible for the machine learning emulator to be much faster than the physics-based simulations while still being accurate, because it can learn emergent patterns in the data.

This approach can be used to emulate both weather and climate simulations. In the second part of the tutorial, we demonstrate how to used this approach to predict month-ahead sea surface temperature.

Part 1: Tutorial for Timeseries Modeling

Open the following notebook on Google Colab. You can also run the notebook on your own local machine running or HPC account running Jupyter, but the notebook requires the Tensorflow package so we recommend using Colab if you don’t already have this installed.

Part 2: Tutorial for Timeseries Modeling of Spatial Data

Now we extend the model from Part 1 to include spatial dimensions. You will train a convolutional neural network to emulate a climate simulation model called the Canadian Earth System Model, and use it to forecast Sea Surface Temperature 1-6 months in advance. The following tutorial is a simplified version of the work presented in the 2020 AAAI workshop paper, Nikolev+, Deep Learning for Climate Models of the Atlantic Ocean.

The notebook requires two files. Download these files from google drive, then upload to colab:

Citations

- Figure 1: https://www.australianenvironmentaleducation.com.au/education-resources/climate-vs-weather/

- Figure 2: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-temperature

- Figure 3: https://www.statista.com/chart/19418/divergence-of-ocean-temperatures-from-20th-century-average/

- Figure 4: Image courtesy of Paul Ullrich, University of California, Davis

Key Points

Climate science is largely limited by the minimal data collected on timescales necessary to assess long-scale patterns.

Understanding and prediction of climate is very computationally expensive and still very limited.